EVs on Life Support (Part 2): China, the EV Manufacutring Powerhouse

China established itself as an EV manufacturing powerhouse at a substantial cost yet, apparently, without the same drive for environmentalism that has swept the West. Why spend all this money then?

The first part explored the reasons behind Norway’s electric vehicle (EV) adoption success story. Norway stands to reduce carbon emissions (the stated objective of the Government’s policy) from each vehicle transitioned to electric by about 99.5%, largely due to its hydro-powered electricity grid. The country managed to substantially improve EV adoption by using incentives that yielded a massive auto market distortion. EVs that are generally more expensive to build the conventional vehicles are, in Norway, less than half the price of a conventional vehicle. Incentives are costing the country about US$ 4 billion per year. While the government’s intention is to reduce incentives, removing them, even partially, may essentially kill the market for BEVs.

China’s, a country that doesn’t enjoy Norway’s electricity fuel mix (spoiler alert, it’s mostly coal) nor has made real commitments towards emissions reduction goals that has however spent more than USD 230 billion to support EV adoption. Both China’s and Norway’s EV markets are on a lifeline, albeit perhaps for different reasons.

China’s EV sales: Separating Facts from Ads

China’s new energy vehicles (NEV) sales in August 2024 topped 1 million units prompting a flurry of news items commenting on the country’s ‘stellar’ performance (for some reason, ‘stellar’ seems to be the adjective of choice describing positive progress in EV sales ). While the feat is impressive, it is worthwhile examining the numbers in further detail. First things first, NEVs are an aggregation of battery electric vehicles (BEVs) and plug-in hybrid vehicles (PHEVs). Hence, although impressive, actual sales of BEVs were just shy of 650,000 units while PHEVs were over 430,000 units. PHEVs have internal combustion engines (so not really ‘new energy’) and relatively small batteries and driving ranges (up to 30 kWh and +/-100km range). Hybrids have been on the auto market already for decades, although perhaps not as much the plug-in variety.

Of the 650,000 BEVs sold in August, approximately 100,000 vehicles are in the mini or supermini categories meaning they have batteries as low as 9.2 kWh. Mini or supermini EVs are slightly bigger than the Citroen Ami, which Citroen themselves don’t call a car, rather an electric quadricycle. This is important because it is difficult to then compare EV sales on a one-to-one basis between China and European countries.

Conflating BEVs and PHEVs together as well as the mini and supermini vehicles in one large sales pool certainly gives the impression that China’s auto market is predominantly electric and makes it more straightforward to create graphs such as the ones below. While these figures help make the case for impressive headlines, they do require some attention to detail to better understand market dynamics.

As a sidenote on mini and supermini EVs, it is quite likely that these vehicles are the first vehicle for some buyers as their prices (as low as US$ 4,000) make them affordable for a larger strata of the Chinese population. These vehicles provide limited mobility. However, when compared to walking or cycling, one may prefer the warmth and comfort of an electric quadricycle to walking or cycling on a windy or rainy day. The point I am making is about statistical equivalence with other countries rather than purely dismissing the worth of this class of vehicles from a mobility perspective.

The Cost of EV Adoption Success

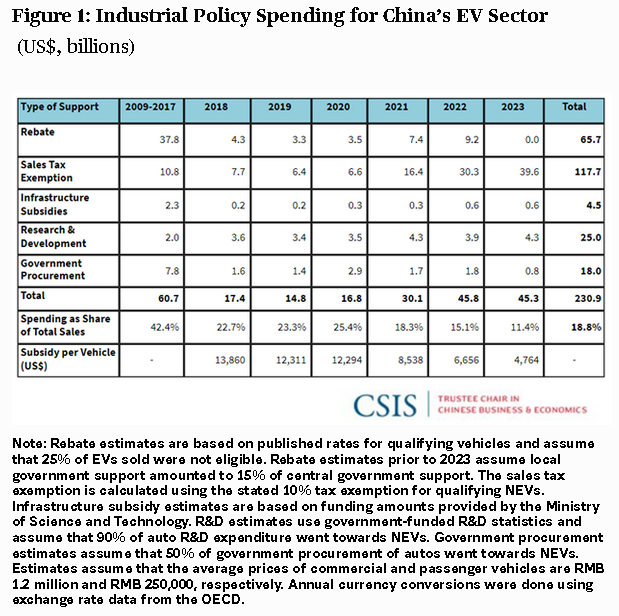

An aspect is that is less often discussed is the cost of the increase in new energy vehicle (NEVs) sales. The Centre for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), a U.S.-based think tank estimated that EV subsidies cost China more than US$ 230 billion between 2009 and 2023, 40% of which was spent in 2022 and 2023. Up until 2022, potential buyers could be eligible for a maximum subsidy of 12,600 yuan (US$ 1,750) per vehicle for a BEV and 4,800 yuan (US$ 670) for a PHEV.

From 2024 onwards, China had committed to a 520-billion-yuan (US$72.3 billion) package of tax breaks over four years for new energy vehicles. This package includes a purchase tax exemption for NEVs amounting to as much as 30,000 yuan ($4,170) per vehicle. As in Norway, other E.U. countries or the U.S., the government heavily subsidised mainly electric vehicles to facilitate their adoption. China currently provides a cash subsidy of as much as 20,000 yuan (US$2,800) for trading in conventional cars to buy NEV, a subsidy that it has doubled just 2 months ago since its introduction in April 2024.

There are other, perhaps less evident costs. Shortly after news came out on the 1.1 million NEVs sale in August, the China Automobile Dealers Association (CADA) released a report which indicated that car dealers in China had incurred a 138 billion yuan (US$ 20 billion loss) between January and August 2024. CADA highlighted concerns about an ongoing price war between dealerships and that car dealers had been forced to sell vehicles at a discount of 17.4% in August! August was a terrific month for NEV sales, and it’s no surprise given the discounts and subsidies. While this is not a direct cost to the Chinese government, it may become one as CADA requested government financial support for dealerships.

The question you may have is why would the Chinese government pump so much money in this particular sector? Is it care for the environment or are there other reasons?

Environmental Impacts of EVs in China

Are China’s main reasons for pushing electric vehicle adoption environmental? That’s doubtful.

Unlike Norway, China’s electricity fuel mix is primarily fossil fuel-based. More than 60% of the country’s electricity is generated by coal. It is true that the country’s wind and solar energy generation have grown significantly. Between 2022 and 2023, wind and solar generation has grown by 280 TWh. In the same years however, coal generation has also grown by 340 TWh. Hence, the country’s electricity emissions grid intensity has improved by just 0.6% between 2022 and 2023, currently standing at 582 g CO2-e/kWh.

The relatively high electricity grid emissions intensity means that the emissions reductions realised by introducing electric vehicles instead of conventional vehicles may not be necessarily high. A 2021 paper explored this issue through a life-cycle analysis. The authors concluded:

There are significant differences in the GHG emission reduction and energy saving effects of EVs in various regions of China. In South China, due to the high proportion of renewable energy power generation (55.11%), the life cycle GHG emissions and fossil energy consumption intensities of EVs are approximately 30.98% and 43.16% lower than those of TFVs [traditional fuel vehicles], respectively. For other regions with a high proportion of coal-fired thermal power generation, such as the northeast, northwest, and central regions of China, the full life cycle GHG emission and fossil energy consumption intensities of EVs are only about 0.47%–11.78% and 20.08%–28.71% lower than those of TFVs, respectively. Especially in North China, thermal power accounts for 85.52% of total electricity generation, making the EV's life cycle GHG emission intensity slightly greater than that of the TFV. As the proportion of China’s renewable electricity generation continues to increase, the advantages of EV in energy conservation and emission reduction will become more and more significant.

This paper’s findings are still relevant today even if it was published in 2021 as China’s grid emissions intensity has only decreased by about 3 % since then. The traditional caveat that as more renewables come online, the EV emissions advantage will grow ignores that the fact that more EVs will also increase the electricity demand and that electricity will have to come from somewhere. Wind and solar generation are just not growing fast enough to satisfy the extra electricity demand and compensate for eventual fossil fuel generation withdrawal. The expectation that the EV emissions advantage will drastically improve in the short- to medium-terms (say next 10 years) is sophistry.

EV Manufacturing, A Matter of Sovereignty?

Perhaps a more plausible reason for China’s focus on EV manufacturing may be one of enhancing it’s own sovereignty in the auto and other sectors. Two aspects are relevant:

Oil & Gasoline Consumption

Battery Production

Oil & Gasoline Consumption

China consumed 16.5 million barrels/day in 2023 and imported roughly 11.3 million barrels/day or close to 70% of its consumption needs. 27% of the oil refined in domestic refineries is used to produce gasoline. For every 1 million BEVs that replace conventional vehicles, gasoline consumption is expected to drop by approximately 1.1 million tonnes per year. This is one reason why the International Energy Agency (IEA) forecast that China’s peak gasoline demand will occur in 2024.This doesn’t necessarily mean that the country’s oil consumption will decline. However, it opens up opportunities for refining other types of products from oil such as petrochemicals particularly those used in the production of photovoltaic panels and other renewable energy sources.

Battery Production

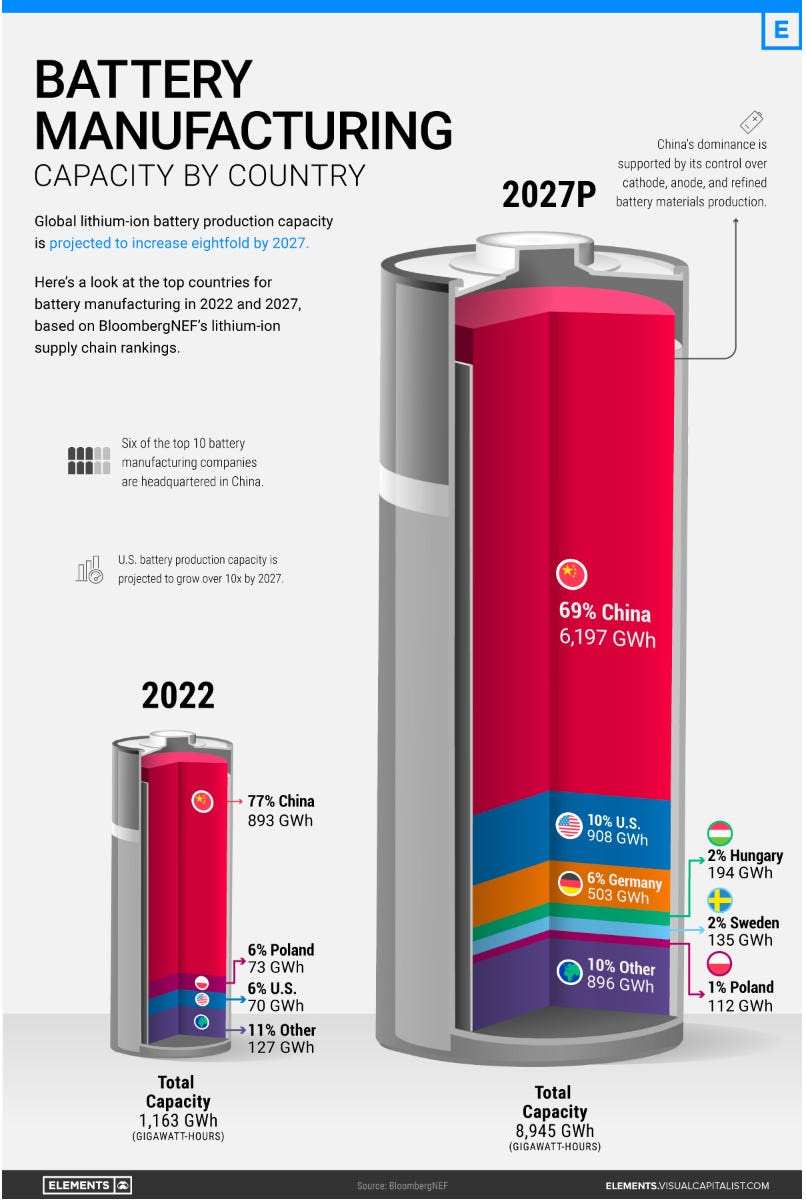

China already produces 77% of the world’s batteries. Battery production is projected to increase 8-fold by 2027. It is highly likely that much of this demand will be swept up by battery electric vehicles. However, BEV sales seem to be at the whim of government policies and subsidies. Not long ago, the E.U. imposed additional import tariffs on Chinese BEV manufactures. China may well be capitalising on its growing internal demand for vehicles and its battery production capacity thus ensuring a greater share of its vehicle production satisfies internal demand and thus stays under the country’s control. After all, it’s much easier to oversee internal demand than it is to navigate the maze of legislation, political interests and supply chain challenges in export markets.

More Than One Reason to Incentivise EV Adoption

China’s interest in EV adoption appears much more oriented towards economic growth, sovereignty and manufacturing utilisation rather than environmental and emissions reductions principles as was the case in Norway. The key similarity with Norway, albeit somewhat less extreme, is the incentive-based EV adoption strategy both countries adopted to ultimately distort the consumer auto market in favour of EVs. This artificial distortion has successfully shifted demand for personal vehicles from conventional vehicles to BEVs. However, it has done so at a substantial financial expense. Although governments may now want to reduce EV-related incentive expenses, that comes with a great risk, that the demand for EVs will collapse. No doubt, representatives from both China and Norway are watching what has been happening in the U.S. and European auto market quite closely.

The next (and final) part will look at answering three main questions:

Why do consumers need convincing to shift to EVs?

What happens when the plug gets pulled from an EV market on life support?

Why should all this matter for you?

Stay tuned for EVs on Life Support (Part 3): Europe’s EV unplugging chaos.