When Technology Plays an Active Role in Airplane Crashes

This edition covers recent developments in the Boeing 737 MAX case, BMW CEO's warning against excessive focus on electric vehicles and, "strategies" to reduce the production price of hydrogen

The 737 MAX, Fraud and the Role of Technology

Although Boeing recently been in the news for its 737-800 crash in China, an investigation that seems to have hit a dead end, there is another ongoing story that seems to keep on giving: the 737 MAX. In 2018 and 2019 two Boeing 737 MAX airplanes (Lion Air Flight 610 and Ethiopian Airlines Flight 302),crashed shortly after take-off leading to the grounding of the fleet until the investigation was completed. In January 2021, the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) settled the investigation into the crashes with Boeing for 2.5 billion U.S. dollars in which Boeing admitted to criminal misconduct for misleading regulators about the Manoeuvring Characteristics Augmentation System (MCAS) installed on the 737 MAX, laying most of the blame on its former Chief Technical Pilot. Despite the victims’ families being awarded US$ 500 million of the 2.5 billion dollars, some of the victims have called the DOJ to rescind the settlement which has, so far, protected Boeing from facing criminal charges. Furthermore, in March 2022, Mark Forkner, Boeing’s former Chief Technical Pilot overseeing the 737 MAX programme was acquitted of defrauding regulators. There are several valuable lessons to be learned from the Boeing case around assumptions for technology and legislative frameworks for technology-assisted decision-making which I’ll explore in more detail.

Correcting Design Changes with Digital Technology

The 737 MAX is the successor to the 737-800, one of the most commonly used aircraft in commercial aviation. Although the design of the 737 MAX resembled that of previous variants, one key difference was that the engines were enlarged. This enlargement caused the aircraft to be tail heavy and have the tendency to have point up on certain manoeuvres. To counteract this tendency, the Manoeuvring Characteristics Augmentation System (MCAS) was designed by Rockwell Collins and installed to automatically activate the plane’s horizontal stabilisers when certain conditions were met.

The MCAS was originally intended to be active only in certain high-speed manoeuvres, well outside the plane’s expected operational conditions. Hence, reference to the system was eliminated from pilot training materials. Over time, the MCAS scope expanded to speeds well within the regular operational conditions of the aircraft. However, these changes were not reported to the FAA – hence the charge of misleading regulators. Why would Boeing do such a thing? Changes to the way in which an airplane operates determines the pilots’ minimal training requirement. The bigger the changes, the more training and the more expensive training required. By not reporting the expanded MCAS scope, Boeing secured a Level B training requirement (requiring a couple of hours of extra reading for pilots to be able to fly the 737 MAX) rather than a Level D or above which required pilots to physically spend time in flight simulators. To some extent, this helped shore-up existing 737 operators from competition with Airbus.

Technology Implementation Failure?

There were also technological issues which have been largely overlooked in the DOJ’s investigation, as veteran pilot’s “Sully” Sullenberger statement in front of the House Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure reveals. First, MCAS relied on a single angle of attack sensor (rather than two), creating a single point of failure. A failure of the angle of attack sensor could thus trigger the unnecessary activation of the MCAS. Second, MCAS could autonomously operate the horizontal stabiliser (to full nose-down position) without providing any feedback in the pilot’s column. Once activated, there was no way to turn off the MCAS until the angle of attack was corrected within parameters. The combination between a single, potentially faulty, input and lack of feedback to pilots proved to be a fatal one. Yet, this story line seems to be completely overlooked in the DOJ’s investigation. Why?

The why question brings us to the crash victims’ request to rescind the DOJ settlement and investigate Boeing for criminal charges. By settling the investigation on conspiracy to defraud regulators, the DOJ avoided to investigate the design errors in the MCAS. Maybe they have a point. The U.S. and most countries have law and justice systems designed to assess human behavior. Who is to blame when a software tool behaves improperly? And, more importantly, who is to blame when a software tool behaves as designed with improper inputs or assumptions? These aren’t new questions, but the answer seems to be unequivocally the operator and rarely, almost never, the owning organisation or software manufacturer (Rockwell Collins is almost never mentioned in court proceedings).

The Boeing example isn’t unique. In the fatal crash involving Uber’s self-driving car in 2018, Uber was not criminally charged despite the U.S. National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) finding that “Uber’s autonomous vehicles were not properly programmed to react to pedestrians crossing the street outside of designated crosswalks”. Indeed, the NTSB emphasised these issues which contributed to the crash: failure of the operator to monitor the vehicle, inadequate safety risk assessment, ineffective vehicle monitoring, inability to address automation complacency etc. Although Uber was not criminally charged, the back-up driver is currently on trial for negligent homicide.

Lessons and Legal Frameworks

Although people died, partly as a result of technology failure, it is incredibly difficult to assign blame. Imagine a scenario where Boeing was criminally charged. Who goes to jail? The CEO, the software manufacturer, the test pilots? After 10 crashes, who would work for a company while risking jail for issues that they may not even be aware of. What’s the crime? Negligent homicide (who exactly was negligent), bad software engineering (what are the laws for good software engineering), insufficient testing (which are all possible test cases that should be considered)? All these questions seem to have no answer under the current legal frameworks.

Investigators therefore look for visible (however weak) human-related causal links – if the chief test pilot would have reported the MCAS expanded scope, there would have been more pilot training and crashes would be avoided, if the backup operator in the Uber would have been watching the road, the crash would be avoided. How would more training prevent crashes if the MCAS intervention cannot be overridden by pilots? How long until another distracted autonomous vehicle operator highlights programming errors? These are questions beyond the regulators’ and investigation’s scope.

There are several key take-aways from the 737 MAX story:

The one source of truth can fail to tell the truth

As humans we rely on multiple sensor inputs to judge a situation. Where one eye can deceive, two are better and other sensory inputs can help. The same is true for digital tools. Acting based on the inputs of a single sensor (or type of sensor) assumes that the sensor(s) is working and working correctly. Digital tools can operate perfectly based on faulty inputs, producing results that make no sense. Before relying on a tool’s output, its inputs must be validated!

Tesla’s vision-only approach for its self-driven cars may well prove to suffer from the same issues as MCAS. While camera guidance has so far proven the most promising avenue for self-driving, its performance drops in poor weather conditions. Similarly, the vision-only driving assumption is that cameras are operating correctly. Is it possible that the US$ 12,000 full self-driving feature be rendered useless by a couple of strips of tape covering the cameras?

Technology can harm but legal frameworks are lagging

As technology becomes increasingly embedded in more aspects of life, it also gets increasingly more autonomous. Autonomy should come with some level of responsibility. However, software tools seem to take all the fame and none of the blame. Be wary of software tool purporting to assist decisions – the tools are not “responsible” for the outcome, you are. The main reason for that seems to be the inability of legal frameworks to differentiate between poor software implementation and poor decision-making.

In Other News

Jet Fuel Savings

The U.S. Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) released its Aviation Climate Action Plan containing a series of emission reduction measures. Amongst these measures, the FAA suggests an ‘optimised profile descent’ to be used when aircraft are preparing to land. Aircraft commonly descend in steps, with the transition between steps directed by control towers. The optimised descent essentially allows aircraft to glide towards landing, thus reducing fuel consumption during the descent.

This measure might actually work in producing immediate and tangible results both in terms of emissions and fuel consumption savings. Most emission reduction efforts seem to be concerned with a not-too-distant future when fossil fuels will have been replaced by renewable energy. In the meantime, these types of operational and technical improvements can make a real impact today.

All Batteries in One Basket

BMW CEO Oliver Zipse warned recently against excessive focus on electric vehicles to the detriment of other powertrains (including the internal combustion engine). One of his key arguments was around the limited number of countries where clean energy metals are mined and processed. This graph highlights his concerns quite well. I’ve also written extensively about clean energy metals mining and processing capacity issues here.

Hydrogen Cost Reduction Strategies

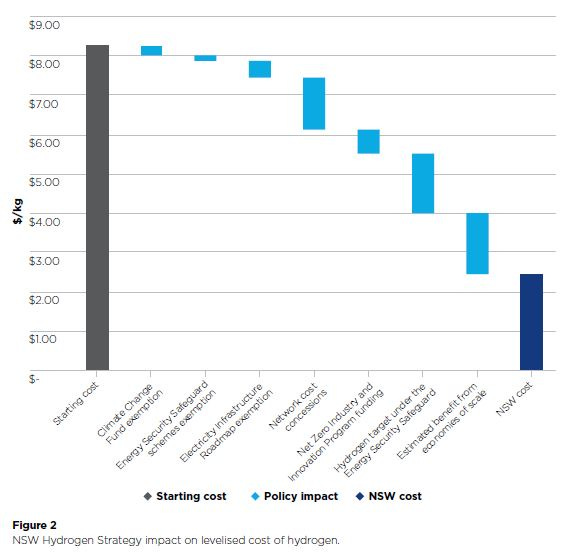

The NSW Government in Australia recently released its Hydrogen Strategy where it highlights several key ambitions including lowering the price of hydrogen to under AUD 2.8/kg by 2030. This is an ambitious objective considering that current estimates for producing hydrogen in NSW place this at AUD 8.2/kg. So how would this 66% reduction be achieved in just 8 years? Subsidies. The way to lower retail prices is effectively for the government to become an intermediary and sell at a loss because… I’m still struggling to find an explanation.

Meanwhile, this image seems to capture the gist of this hydrogen strategy.